Stream and Riparian Physical Habitat Assessment for the Roaring Fork Watershed

The Roaring Fork Stream Health Initiative is a science-based assessment of the in-stream and riparian habitats of the Roaring Fork River and its major tributaries. During three years of field work, from 2003 to 2005, the Stream Health Initiative conducted a physical habitat assessment on approximately 185 total stream miles in the Roaring Fork Watershed, which included the Roaring Fork River from its headwaters to its confluence with the Colorado River, as well as significant portions of Lost Man, Castle, Maroon, Brush, Snowmass, Cattle and 4-Mile Creeks, and the Frying Pan and Crystal Rivers. The purpose of the project has been to create a comprehensive inventory of in-stream and riparian habitat quality in the watershed; to identify stream segments in need of restoration and protection; and to assist local jurisdictions, non-government organizations, and private landowners in the development of sustainable management strategies for in-stream and riparian resources in their area.

For more information, contact John C. Emerick or Delia G. Malone, SHI founders, at 970-963-2143, or jemerick@sopris.net.

INTRODUCTION

The Roaring Fork Stream Health Initiative is a science-based assessment of the in-stream and riparian habitats of the Roaring Fork River and its major tributaries. During three years of field work, from 2003 to 2005, the Stream Health Initiative conducted a physical habitat assessment on approximately 185 total stream miles in the Roaring Fork Watershed, which included the Roaring Fork River from its headwaters to its confluence with the Colorado River, as well as significant portions of Lost Man, Castle, Maroon, Brush, Snowmass, Cattle and 4-Mile Creeks, and the Frying Pan and Crystal Rivers. The purpose of the project has been to create a comprehensive inventory of in-stream and riparian habitat quality in the watershed; to identify stream segments in need of restoration and protection; and to assist local jurisdictions, non-government organizations, and private landowners in the development of sustainable management strategies for in-stream and riparian resources in their area.

METHODS

The major streams and rivers of the watershed were divided into segments, based primarily on geologic or geomorphic characteristics of the watershed portion where the streams were flowing. Each segment was further divided into reaches, based on various characteristics, such as stream gradient, riparian ecosystem type, and disturbance. In all, the project evaluated 17 segments comprised of 140 stream reaches.

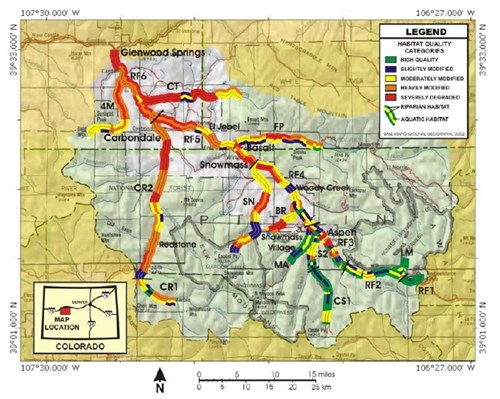

During the assessment, project personnel conducted a field evaluation of each stream reach using established protocols, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Rapid Bioassessment Protocols for physical stream habitat, the National Resource Conservation Service Riparian Habitat Assessment methods, and Bureau of Land Management Proper Functioning Condition procedures. These protocols allowed each reach to be given a score for in-stream and riparian habitat quality. Based on these scores, the riparian and in-stream habitat is placed into one of five habitat quality categories: high quality, slightly modified, moderately modified, heavily modified, and severely degraded. Each segment could then be mapped showing the stream and riparian habitat quality for every reach in the segment.

RESULTS

Both in-stream and riparian habitat quality was better in headwater areas, especially on the upper Roaring Fork segments and on the upper tributaries including Maroon, Castle, and Lost Man Creeks. In these areas, the riparian and in-stream habitats were mostly in the high quality or slightly modified categories. Moving downstream from these headwater areas, the cumulative effects of roads, land development, agriculture, and pollutants clearly have an impact on stream and riparian habitat quality. The lowest Roaring Fork segments and the lower tributaries are dominated by habitats in the heavily modified and severely degraded categories.

A generalized habitat quality map of the Roaring Fork Watershed, showing the reaches assessed in this project.

Each reach is depicted as a band of three stripes, with the outer stripes representing the habitat quality of the right and

left banks (looking downstream), and the center stripe representing the in-stream habitat quality.

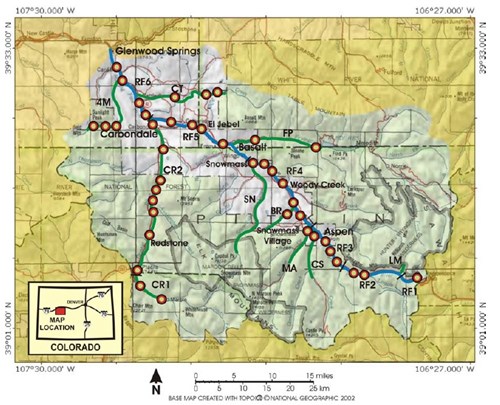

CONSERVATION AREAS OF CONCERN

During the assessment, we began to realize that many areas in the watershed are, or have the potential to be, especially valuable to wildlife, but are at risk due to current or potential threats to stream and wildlife values. We have designated these areas as Conservation Areas of Concern and believe they should be given high priority with regard to conservation efforts in the watershed. Some of these areas are currently in ecologically sustainable condition, while others are not and are in need of management action to restore ecological health. Regardless of the current condition, each area has especially important wildlife potential. These Conservation Areas of Concern are shown on this map, and are described in the appropriate segment and reach descriptions in the catalog.

The map above shows the location of 41 Conservation Areas of Concern identified by the project.

TOP TEN THREATS TO A HEALTHY STREAM

Part of the assessment of each stream reach was to document factors that were affecting stream health at the time of the assessment, or were likely to be a significant threat in the near future. While the threats varied from reach to reach, the reoccurrence of many of the threats was notable. Our “top ten” threats for the watershed as a whole are listed below, roughly in the order of their importance based on the number of reaches where each was documented:

- Dewatering: Due both to trans-basin water diversions and in-basin diversions, primarily for agriculture. Loss of water and reduced flow decreases the stream’s ability to carry sediment and maintain good physical habitat for fish and stream insects, and it reduces the effect of dilution on waterborne pollutants.

- Recreational Disturbance: Primarily from fishermen and rafters, causing trampling of riparian vegetation and development of “social” trails that degrade riparian habitat and destabilize stream banks.

- Road Disturbance: Especially in narrower tributary valleys, the presence of roads and adjacent rip-rapped stream banks has effectively channelized the streams and eliminated riparian vegetation.

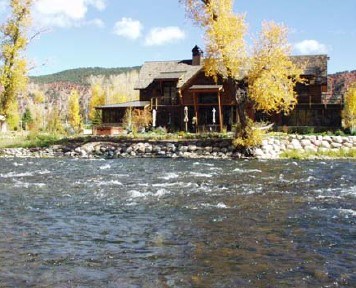

- Residential and Commercial Development in Riparian Zone: This includes building construction and landscaping “to the water’s edge”, eliminating riparian vegetation, often requiring bank armoring, or rip-rapping, with boulders to reduce erosion.

- Noxious Weeds: Land disturbance and removal of native vegetation are prime causes for the invasion of noxious weeds, such as Canada thistle, nightshade, poison hemlock, houndstongue, and leafy spurge, which often prevent the re-establishment of native vegetation and do little to stabilize stream banks.

- Livestock in the River and in Riparian Zones: Cattle trample riparian vegetation, contribute to eroding stream banks, and degrade in-stream habitat for aquatic insects, plus, their manure contributes to nutrient enrichment of the stream water.

- Nutrient Enrichment: Nutrients, such as nitrates, ammonia, and phosphates, that come from a variety of sources such as private septic systems, municipal waste treatment plants, fertilizers from lawns and golf courses, and agriculture, often lead to excessive algal growth in the stream, and in extreme situations can reduce dissolved oxygen and cause fish mortality.

- Agricultural Elimination of Riparian Vegetation: In wider floodplain areas, riparian vegetation has been replaced by hay meadows. This has often led to stream bank erosion, down cutting of the river channel, and isolation of floodplain soils from inundation during spring floods.

- Stream Channelization: In many places, the stream channel has been confined and often straightened, and the banks typically armored with boulders to prevent erosion. While this practice might indeed prevent erosion in channelized areas, stream energy during spring floods is poorly dissipated and often contributes to erosion and down cutting farther downstream.

- Elimination of Beaver Ponds: Beaver ponds trap sediment and help dissipate the stream’s energy, thus preventing erosion. Also, the natural “boom and bust” cycle of beaver activity in the floodplain contributes to a more diverse riparian habitat, which in turn increases wildlife diversity.

|

|

| Vegetation removal in this golf community has destabilized stream banks, reduced shade that maintains cooler water temperatures and eliminated both aquatic and riparian wildlife habitat. Boulder rip-rap on the banks channelizes stream energy toward the next unprotected area downstream. |

Cattle degrade water quality and destroy riparian habitat. |

CONCLUSIONS

- Stream and riparian quality declines from near pristine conditions in headwater areas to severe degradation in the lower reaches.

- Dewatering of the system through trans-basin and within-basin diversions is a major factor in the decline of stream and riparian habitat quality, by increasing waterborne pollutant concentrations and decreasing the frequency, duration, and intensity of flushing flows during the runoff season.

- Disturbance to the riparian habitat is often one-sided in narrower valleys where highways alongside streams displace habitat, and contribute significant amounts of sedimentation and other road-based pollutants to the stream. This is especially visible in the Frying Pan and Crystal River valleys.

- Throughout the middle and lower parts of the watershed, riparian habitat has been severely degraded or eliminated by residential and commercial development, agriculture, and recreational use. This, in turn, has caused degradation to the adjacent stream habitats.

- In many places throughout the watershed where habitats have been slightly, moderately, or heavily degraded, the disturbance can be arrested and often reversed simply by a change in land management procedures.

- A number of Conservation Areas of Concern have been identified by this project throughout the watershed. These are areas where the habitat is often still in good condition, with significant wildlife value, that warrant immediate efforts for protection.

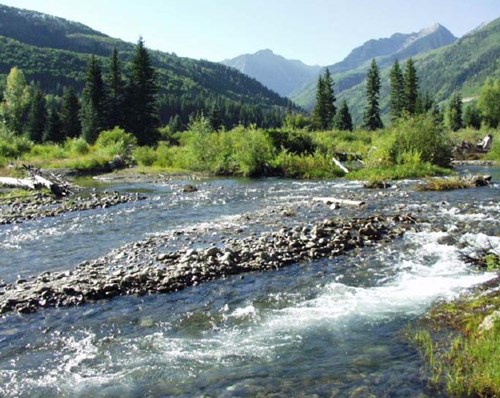

A view of the Crystal River looking south toward Chair Mountain.

In spite of many impacts from land development, agriculture, and mining, the Crystal River Valley

has some of the best lower elevation wildlife habitat in the Roaring Fork Watershed.